Threads

By Amanda Yin

A Noiseless Patient Spider

BY WALT WHITMAN

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

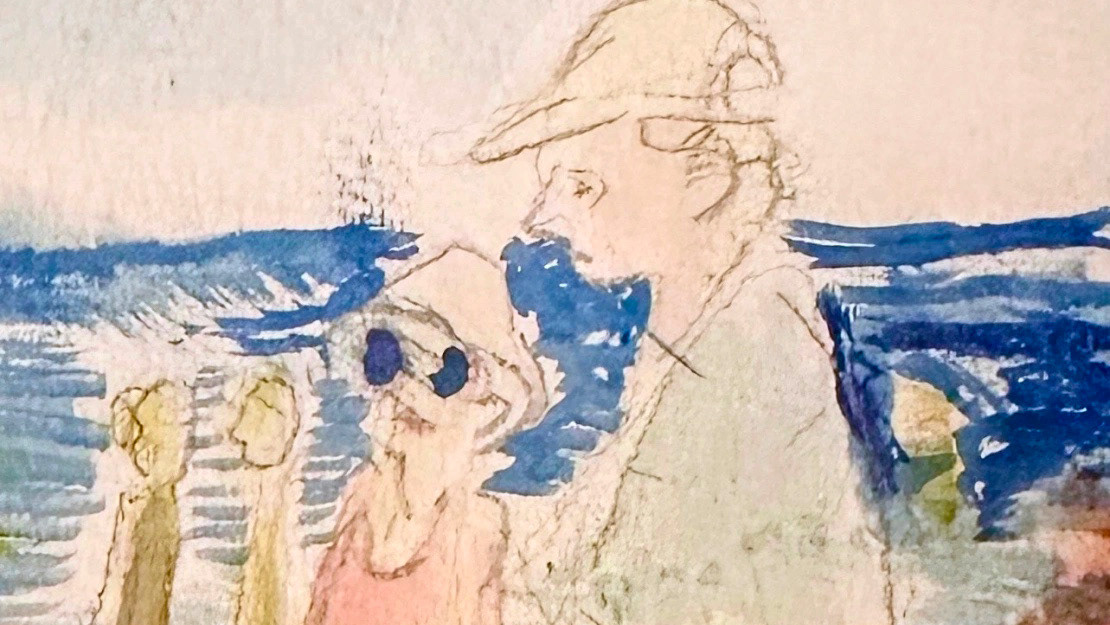

Seeking, 1996

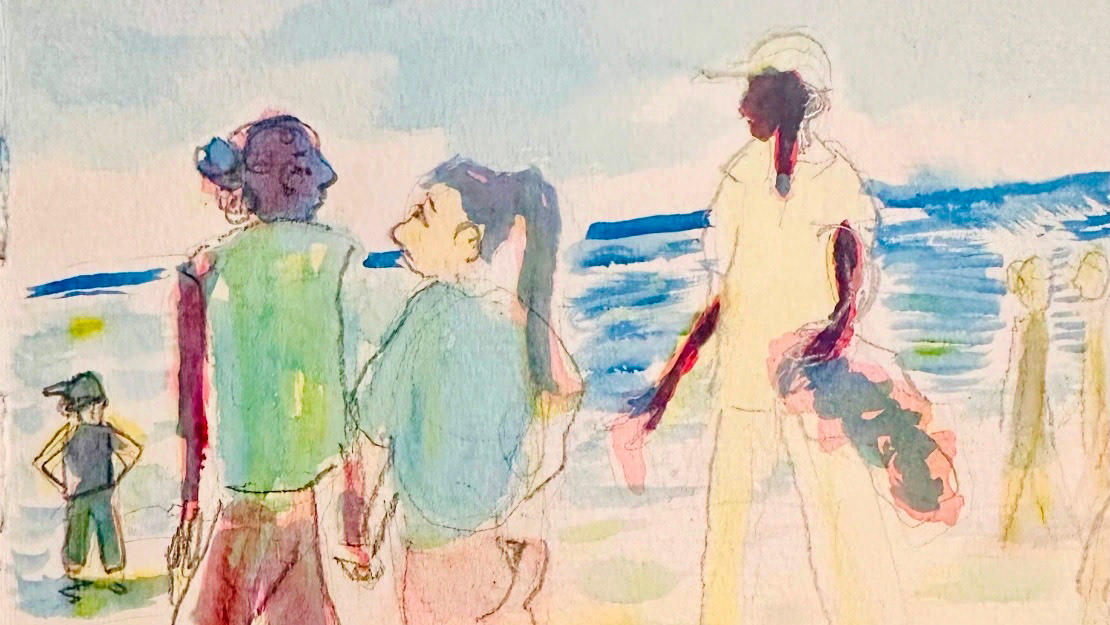

Sketching strangers in public, feels predatory, the ethics of it dubious, (unless one asks permission, and I never ask.) Still, I’ve convinced myself that it’s a victimless crime, with the upside that some of my strongest drawings are quick studies of strangers, reading, asleep, praying – sometimes watching porn. As for the actual ‘practicing’ part of my drawing practice, this is the equivalent of a musician’s scales; it’s how I learned and how I continue to grow.

Like any hunter, I have my spots, church services (any faith or denomination that will let me in), political rallies, the food court at Grand Central, the first or last car on the NYC subway, outside security at Laguardia or Detroit Metro Airports.

Public transportation hubs are where homeless people often sleep. One of the shameful things about being American, a New Yorker or just a human being, is that most of the people asleep outside airport security or on the floor of bus terminals are black men. I am a white woman, in graduate school; I’m not working but still secure in my ability to procure food and always sure that I’ll sleep in a clean, private bed with a locked door. I’m slinking about, surreptitiously sketching vulnerable black men who must sleep and eat in public, subjected to my gaze and everyone else’s: Men our culture collectively gaslights, and discards, then points to as a cautionary tale.

Now that the reality of my sketching practice has sunk in, do you hate me yet? Maybe you should. Sometimes I do. Still, I believe that there is a place for artists here, sketching those society discards. This purpose is not that different than when sketching the denizens of suburban church services, web development client meetings, or any of my more privileged hunting grounds. For me, art always serves the purpose of exploring our common humanity.

By capturing people’s emotions, their posture and expressions, I am assuring myself, and ideally others, of how beautiful we are and of how much more unites us than we acknowledge. I’m also arguing, despite the grave injustices and the horrors that humans are responsible for, that somehow we are still magical creatures. I am trying to say visually (and a little more secularly,) what C.S. Lewis wrote in the essay, The Weight of Glory,,

“There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations - these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit - immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.”

Threads, 1987

Our class mean girl, flanked by her flying monkeys, stalked me between classes and at lunch. I made it easy; I was always alone, shoulders curled towards my chest, carrying too heavy a backpack. I’d gone all in with the ‘just ignore her,’ advice adults dole out. When they surrounded me I’d sit completely still and disappear into myself. Unfortunately this only seemed to provoke.

Central casting couldn’t have dressed me better for middle school victimhood. I’d selected tortoiseshell glasses to twin my hero: my slight, balding, compliance-lawyer dad (our quadruplet pupils, barely visible under miles of translucent glass – identical but for size.) I had the era’s requisite high-volume perm, which I’d sprayed with Sun-In over summer break, a mistake that gifted me with a long, split-end-infested, Donald-Trump-orange, hair-grow-out phase.

There were six kids in my family. Half of us in braces simultaneously. To save money my mom took us to an orthodontist an hour’s drive into the Ohio countryside, to a farm. The farmer, also just out of central casting, seemed to have taken up dentistry as a side-gig. He gave Mormons a big discount, probably a clever strategy to drive volume. My mom didn’t make us call him, “Brother,” so either he wasn’t Mormon himself, creating mystery as to how she’d even found him, or more likely, he was what they called a jack-mormon, not Mormon, but with family ties, fair game for shaming, and/or saving.

As he tightened our braces, the orthodontist would smoke a pipe, making a half-effort not to blow it in our faces (achieving the same results as all half efforts.) Bent over me, close, I'd be overwhelmed by the smoke and the acrid smell I’d later come to associate with unwashed bodies still processing last night’s booze.

This orthodontist was the last holdout for braces with metal entirely circling each tooth, like pigs in a blanket or tiny knights in shining armor, lined up for battle. Normal kids wore braces, with a dainty “X” glued onto each tooth, the enamel mostly still visible, so my gunmetal gray mouth was a source of shame. Still, by refusing to smile, or open my mouth at all, I probably stymied social acceptance far more than all the extra steel.

From the depth of this banal 80s hellscape, one class impacted me forever. Not one semester-long class, a single class — or rather several moments of one single class period of middle school health education. (Raise your hand if something your middle school health teacher said changed your life? Mine is the only hand raised, right?)

I wish I could remember that health teacher's name or his face. I recall an appropriately healthy-looking black guy with close cropped hair, medium caramel skin and a runner’s build. A preppy dresser, he had on a tweed sports jacket with a subtle weave of barely visible plaid lines: A good jacket to wear on a day when you planned to talk about threads.

The health teacher explained that fine, invisible, threads connected us to each other. The more trust we build the thicker and stronger these threads grow, weaving together to form the nearly unbreakable ties that bind parents to their children, best friends, forever.

Cruelty and betrayal could hack away at these threads leading to disconnection; even the toughest ropes can be chainsawed, hit by lightning, or gnawed away by rats. Still, he said, these tiny threads were surprisingly strong. The ropes they formed were built to withstand war, natural disasters, famine.

We form threads with acquaintances too, thinner, stretched, like a spider web, linking us to everyone we have ever known. In the best of worlds, creating a web of safety and community, but occasionally, trapping us too.

My teacher called these threads gossamer threads. (The health teacher didn’t read Walt Whitman’s poem to us, but I found it as soon as Googling was possible, and it's been my favorite poem since.)

After that class I hid in a bathroom stall, feeling my arms and legs, my stomach, hoping to find evidence of those invisible lines, pulling me safely towards anyone at all.

Chisling, November 2024

Before writing this, I read past student’s MFA theses, mining for ideas. From my reading, I noticed that the most common MFA thesis line, and maybe the cringiest, is, “I draw obsessively.” Yet, here I am, fully aware of the power those three have words to annoy, writing them in my own thesis.

What an odd thing to be obsessed with (are we really obsessed or is it as pretentious as it sounds?) Is there a dopamine rush as I tear up my sketchpad and throw it at the wall because I can’t get the nose right? Such behavior has no discernible evolutionary advantage. Surely we’ll be too focused on drawing the jungle to see the tiger creeping up behind a tree.

This activity is not rock guitar; it isn’t social or sexy; it will not increase our chances of passing on our DNA. Even if some desperate soul overlooks the fact that we are only dating them for the free modeling; if against odds we actually do pass on our teen-acne genes, our kid is sure to be eaten by a tiger before they’ll need that Accutane script. (We won’t notice the tiger approaching because we are too busy trying to capture the light on their, still-clear-for-now, chubby, tiger-bait, cheek.)

For me, drawing, even before that fateful health class, helps me figure people out. Maybe by staring at them, surreptitiously recording the slope of their shoulders or the angle of their jawline, I’ll understand them. Then I’ll understand me. Not a logical plan, but what else could I possibly be up to?

In the movie, As Good As It Gets, Greg, the artist character, says the second cringiest line routinely uttered by our ilk. “You are beautiful Carol, You are why cavemen chiseled on walls.”

Watching that movie for the first time, hearing that line (and yes, cringing scraped-blackboard-level,) a vivid image of a screenwriter flashed in my head. Thesaurus in hand, he’s desperately leafing for a less cliche way to say “draw” (“‘Paint,’ still sounds too trite! What about chiseling? Chiseling is an art thing, right?”)

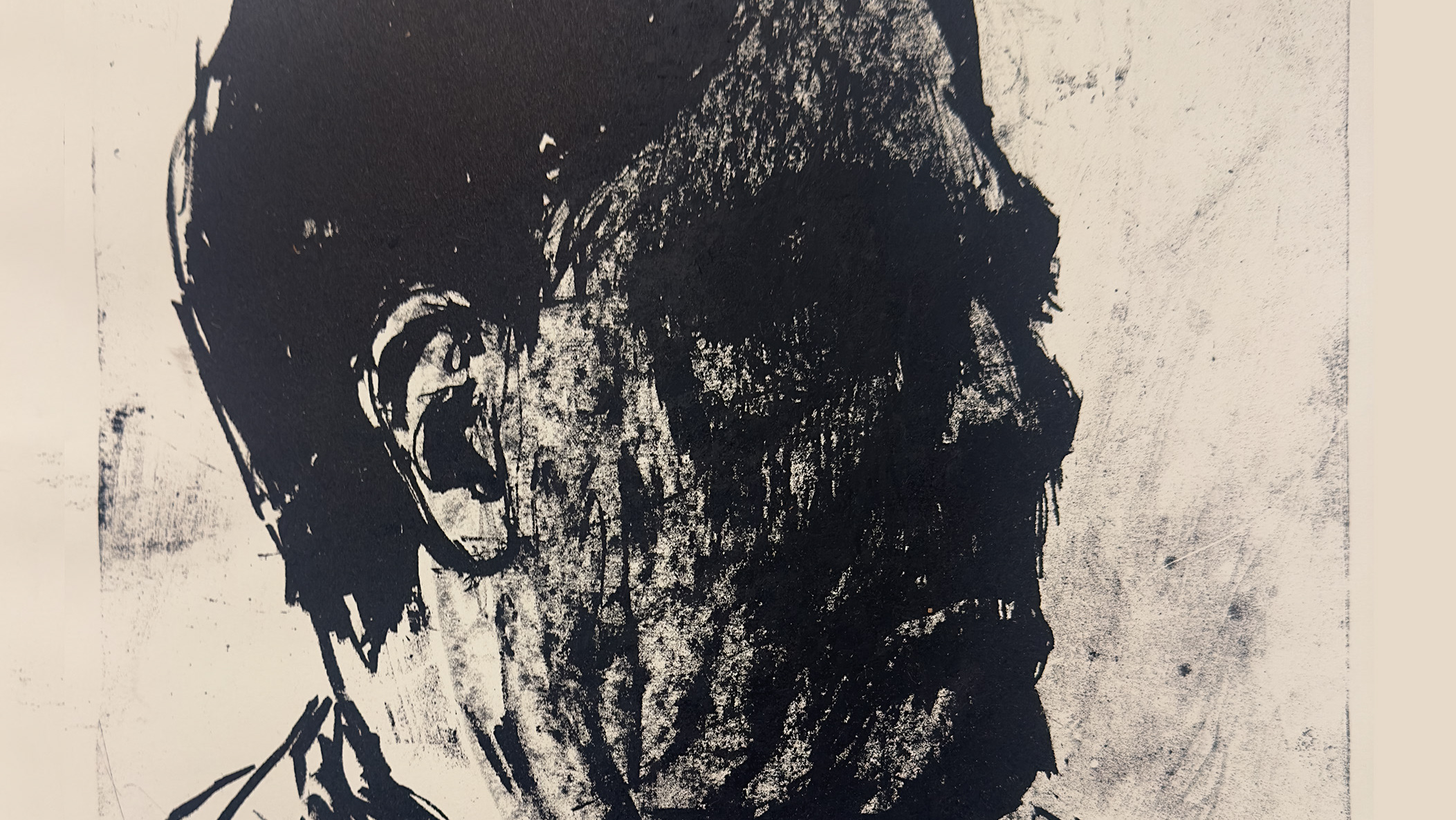

When I wonder what made men “chisel” on caves — or more pointedly why I daily risk my neck staring directly at strangers on the subway while trying to hide the fact that reducing I am the volumes of their face to black scribbles in a tiny notebook — I am also wondering why those scribbles read as that person? That specific person.

Based on our past experiences and information already stored in our mind, our eyes fill in visual blanks, or areas of confusion. The reason we read a line-drawn portrait as a face, and can recognize that face, is the same reason that a circle of dots reads as a circle, not disconnected dots – or why we enjoy looking for recognizable shapes in the clouds .

Gestalt Visual Theory explains that to integrate viewed objects and environments as whole, rather than as isolated parts, the brain groups information based on certain principles: Figure-ground distinction; proximity; similarity; continuity (lines and patterns seem to extend smoothly); and closure (the mind fills in incomplete objects, perceiving them as whole.)

We are born with some innate visual integration. New parents purchase high contrast board books, and mobiles with simple shapes, because research shows that infants perceive simple forms with stark contrasts, indicating that some of our visual processing abilities are innate.

Most of our visual perception, however, develops due to experiential learning. As babies interact with the world around them, moment by moment exposure to stimuli hones their visual perception. Children born blind, but cured through surgery initially are unable to pair a cube felt under a table with the same cube seen on top of the table. Eventually, these children’s visual perception does improve, but never to the level of someone born with eyesight.

The learning experiences and stimuli that each of us are exposed to are as unique as our fingerprints. The location, culture, era, social class and family we grow up in impacts the visuals we are exposed to as our brains develop. The idea that we all see the world differently is not just a cliche, it’s evidenced-based.

Gestalt Visual theory may explain why I love line art so much – and why I love the underpainting better than the finish: Our brain fills in missing visual information based on our past experiences so seeing is far more personal than I’d imagined.

When I look at an Alice Neel portrait. (with expressive mark-making and flatter colors and patterns,) does my brain integrate the work in the same way yours does? Do I see what you see? By limiting information, Alice Neel,

(Toulouse-Lautrec, Egon Schile, cartoonists,) force me to collaborate, to complete their visual sentences.

Photorealism astounds me, but doesn't hold my interest. Now I know why: That perfect painting is spoon feeding me everything. I’m not being asked to play. Photorealism is equivalent to a movie and, (Ugh, am I actually quoting Jane Austen's insufferable Mary?) “I should infinitely prefer a book.”

Lineage, February 17, 2009

I am Alice Neel’s wimpy, bougie, granddaughter. Neel repeatedly choose capturing the human visage over security, often over her kids. Diphtheria took Santillana, her firstborn; she never made it to age one.

Isabetta, her second, was kidnapped to Cuba by Neel's husband Enriquez, and raised by his sisters – but Neel admitted they’d have brought her back if she’d insisted. The guilt drove Alice to attempt her life twice.

At age fifty-four Isabetta succeeded at what her mom failed to do, she climbed onto a seawall, took some sleeping pills and lay down waiting for the tide to come in. Neel hadn’t seen her for thirty years.

When Neel’s lover, the photographer and filmmaker, Sam Brody beat her third son, Richard, Neel never intervened. Hartley, Sam’s biological child and Neel’s youngest, grew up comparatively unscathed, but he still recalls hunger and neglect.

I’m not mom-shaming Neel in writing this. I’m art-shaming myself. Neel was petrified of what she called the “awful dichotomy” of motherhood. When she first married, Neel refused to have vaginal sex, because she feared that childrearing would keep her from painting. Neel knew that Art was a jealous lover, a dark god who demands vestal virginity, or, if not, the sacrifice of her young. Like Neel, the human visage, reduced to weighted squiggles and chicken scratch, is what I’m living for. She served her god faithfully; I’m the one refusing to march Issac up the mountain.

Marks, November 19th, 2024

The joke that therapists pursue their profession to cure themselves applies (direct and humorless) to pop psychology nerds too. I’ve read everything Brene Brown has penned, and “The Body Keeps the Score” sits on my nightstand, but the psychological school that has impacted me most is Victor Frankl’s Logotherapy.

Frankl argues that happiness and true success are byproducts of a deep sense of meaning, and cannot be achieved when pursued for their own sake:

“A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the "why" for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any "how".

In my childhood, I had no “why,” and I was lost. In middle school I began searching for gossamer threads: human connection, friendships, love. When my daughter was born, my longing for connection disappeared, fulfilled, (the umbilical cord is the ultimate thread.) Suddenly I lived to ferry her safely to maturity.

As my daughter gains independence, my purpose has again shifted. Now I feel driven to visually express what I have learned during my previous purpose-lives, what I have hoped for, and dreamed.

I want my work to make the very argument that I am desperate to prove to myself; I am arguing for people, their beauty, their preciousness. It is said that we are a little lower than angels, God’s creatures — but the evidence is against us. Does the Renaissance make up for serfdom? Japanese literature for war crimes in China? Mother Teresa for a society that needs Mother Teresa? Anne Frank’s Diary for Ann Frank murdered? Even the best amongst us occasionally discards single-use-plastic. I want to know that we are not an invasive cancer destroying each other and our sublime blue globe.

I’m willing to ignore the hard evidence. To counter it with evidence of my own. I sometimes fear that my work is like taking pictures of a puppy chewing a boot — to keep from freaking out that he ate your vintage Frye Harnesses.

Of course puppy photos are cute. The beer-gut drunk passed out on the train, not so much. But when you stare intently enough to get a good likeness, something transcends the ugliness. I can see the angel. That guy is beautiful. These marks are the only way I know of to explain why.