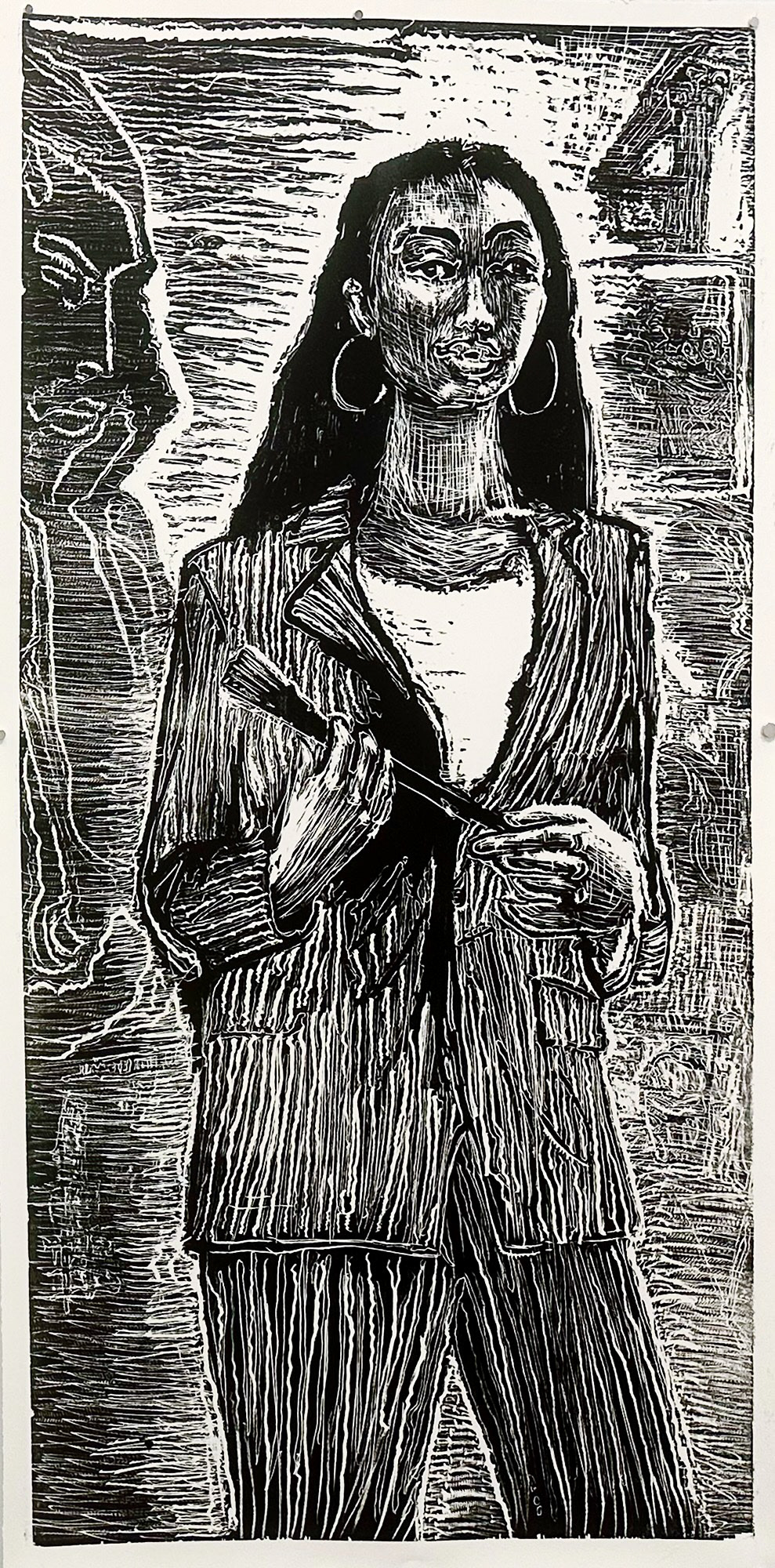

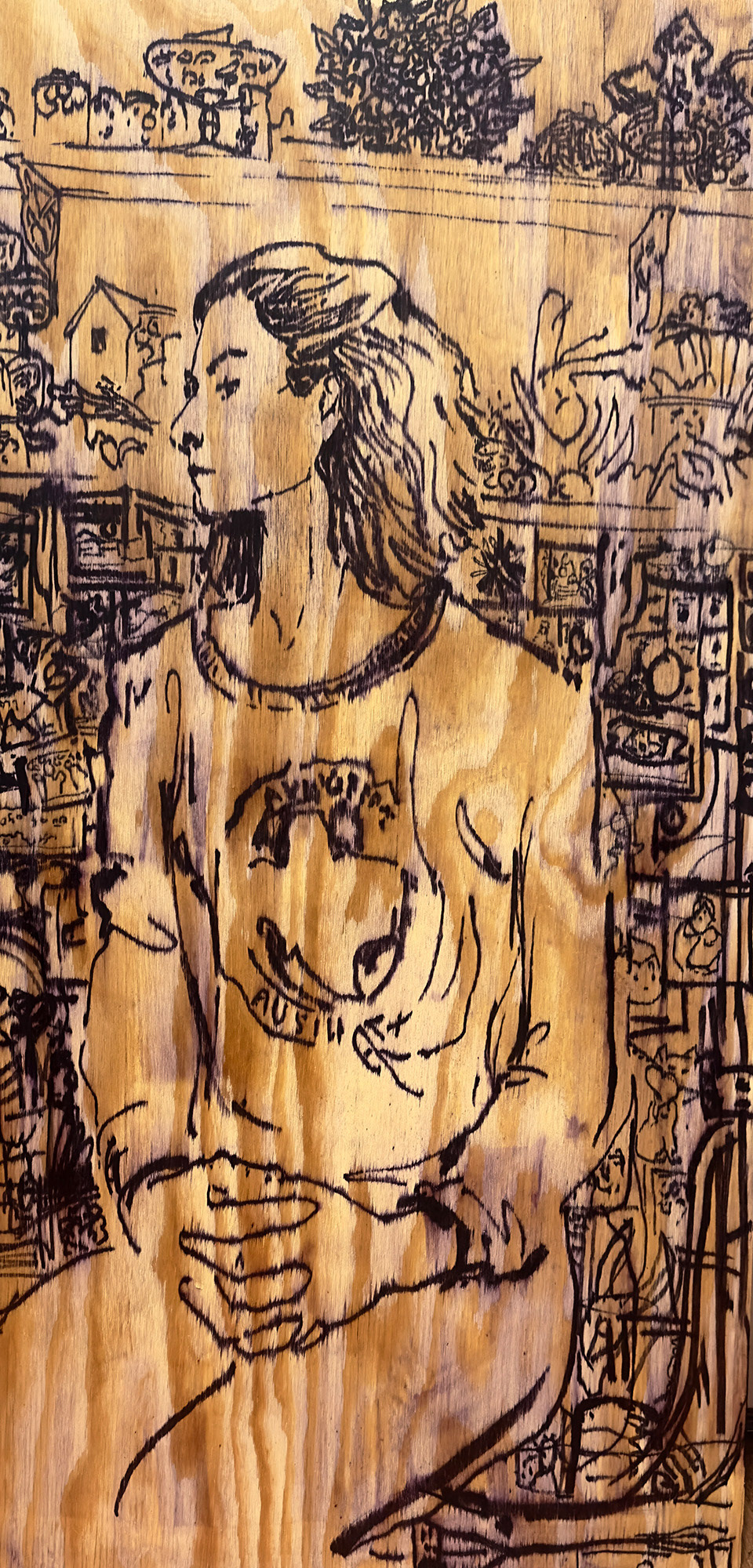

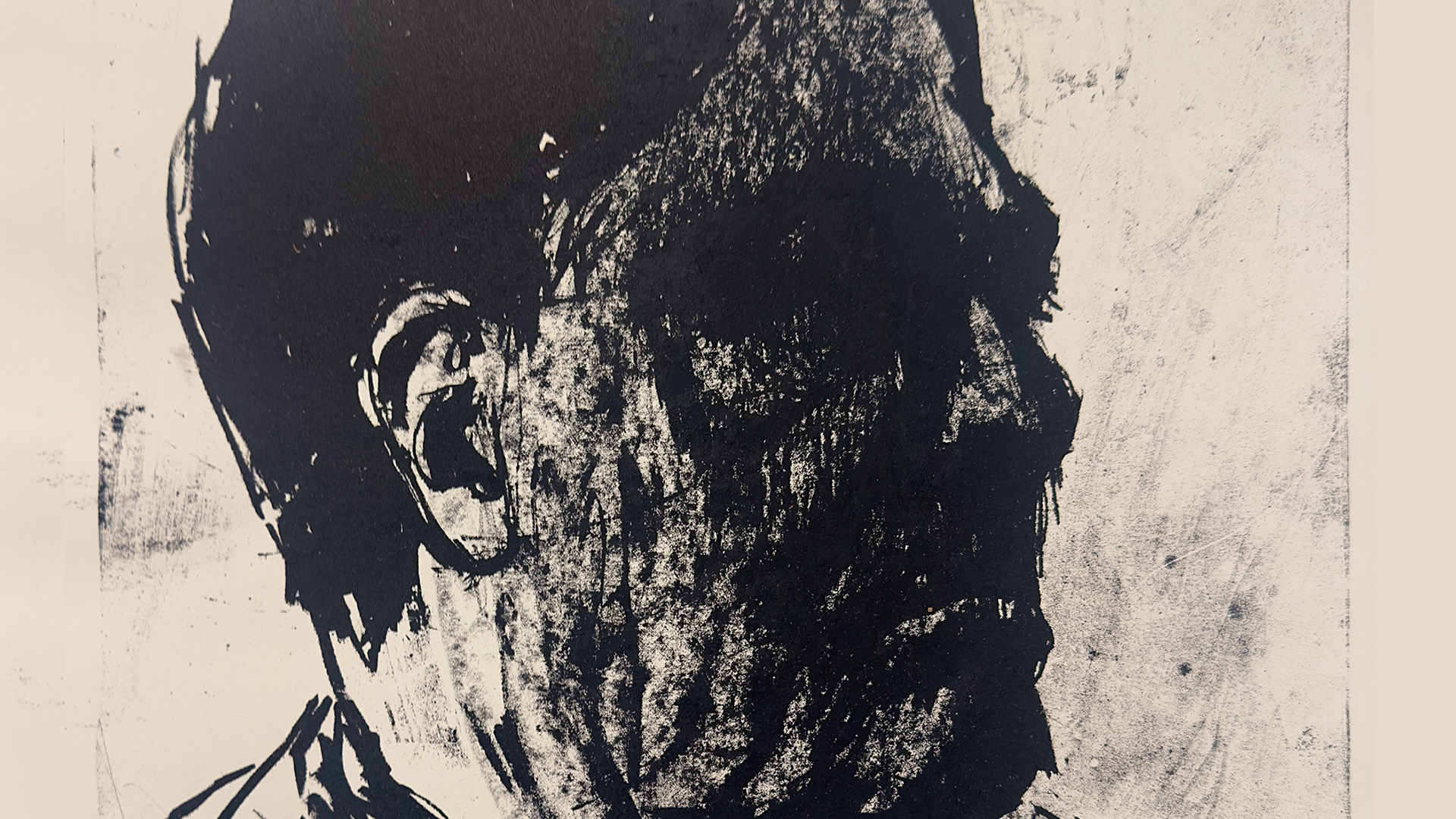

Named after Picasso’s groundbreaking 1907 painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon reimagines his five anonymous, mask-like prostitutes as individuals: real, emerging women artists drawn from life. Each portrait begins as a Sharpie drawing on a wood panel, which is then carved in relief and transformed into a printmaking woodcut.

The woodcut itself is both object and generator — able to produce many versions of itself — not unlike artists and, metaphorically, women. As prints, these portraits become literal “working girls,” a play on Picasso’s subjects and the euphemism for sex workers, but also a nod to creative labor and the fraught cultural expectation that productive artists “sell themselves.”

The choice of wood also references the carved African masks that inspired two of Picasso’s figures, reclaiming their presence and symbolism. Unlike the masked women he depicted, these working artists are unhidden, unmasked, and wholly themselves — highly self-actualizing creatives portrayed in an iconographic style reminiscent of an altar triptych. It is a gesture of reverence, a hope that their work will endure and be celebrated, especially in a culture where female artists so rarely become cultural icons.