Excellence results from education and hard work. This conclusion is at the core of Anders

Ericsson’s research on deliberate practicei, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of the flow stateii, and

Carol Dweck’s growth mindset philosophyiii. Belief in one’s ability to improve, exposure to rigorous

teaching techniques, and the ability to enter a mindful working state are the full DNA of genius;

brilliance is made, not born. These concepts and the research behind them form the core of my

teaching philosophy.

Everyone can create exceptional art by mastering mindful focus, drawing, perspective, design, color

theory, expressiveness, and conceptual thought. Unfortunately, this simple-sounding idea is

complicated in execution. The 1000-hour rule, stating that approximately ten years of practice leads

to excellence, is based on Ericsson’s research, but was simplified and entered pop culture from

Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers. Unfortunately, this famous rule comes with some pretty serious fine

print. Ericsson wrote his book, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, to correct the cultural

confusion (and massive amounts of wasted time) resulting from Gladwell’s simplification. Ten

thousand hours of typical practice will probably just lead to bad habitsiv.

The type of practice needed for life-changing improvement is specific and easy to get wrong.

Becoming a master requires one or two decades of practice in which there is immediate feedback

from mistakes, and the real-time opportunity to correct them. This is because the act of correcting

skills, based on feedback, creates thick myelin sheaths around the synapses that communicate

information about the skill being practiced (much like weight repetition builds muscles). The thicker

the myelin sheaths, the quicker information can be transmitted. When watching Simone Biles do a

double back salto with a triple twist, one sees the amazing results of heavily myelinated sheaths!v

Sports coaching, the trade apprentice system, and music lessons have all utilized deliberate practice

techniques for centuries—with exceptional results. The French Academy also used deliberate

practice. Academic art education, however, exposed one of deliberate practice’s flaws; deliberate

practice teaches excellent skills, but teaching creativity is a different beast. vi

While skills are learned, creativity is innate. Picasso was right: “Every child is an artist. The problem

is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” (How genius disappears as we age is impacted more by

what happens in the first 3-5 years of a child’s life – and is a subject for a different essay.)vii

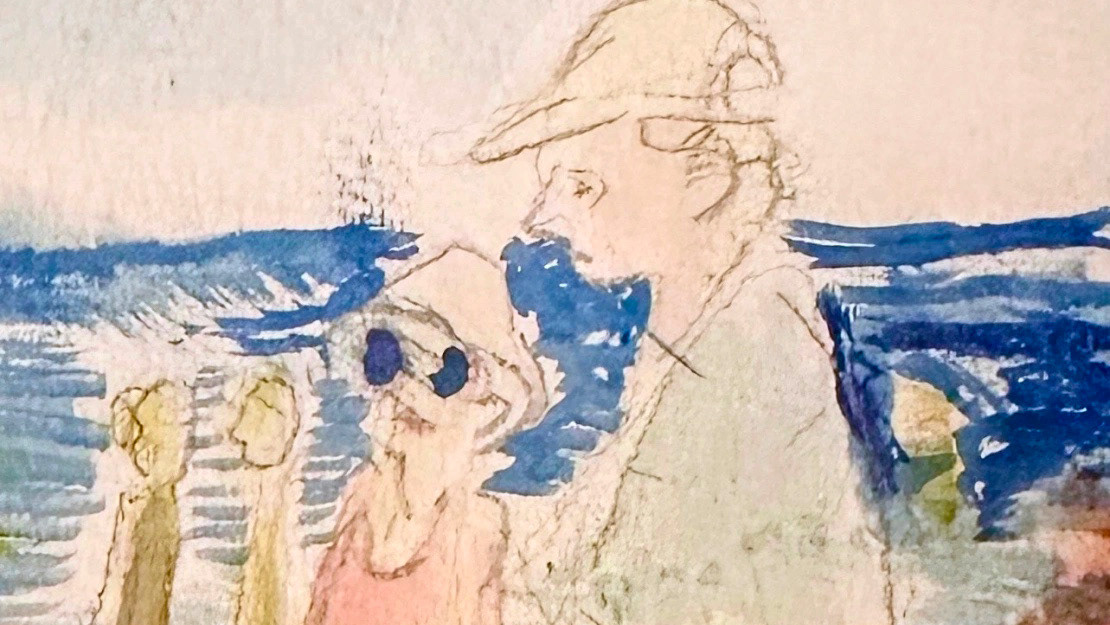

Creativity is better recovered than taught. Recovery comes in part from exposing artists to visual and

philosophical inspiration. More important, however, is teaching the mindfulness and deep focus

skills that allow artists to enter a flow state, enabling them to translate inspiration into creative

output. While in the flow state, described in Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book, Flow: The Psychology of

Optimal Experience, practitioners in any field can access their innate creativity while gaining

remarkable focus, leading to amazing results in their work. While creativity must be recovered rather

than taught, entering the flow state is a learned skill that can be practiced deliberately like any other.

creativity cannot be taught, but the ability to access it can. viii

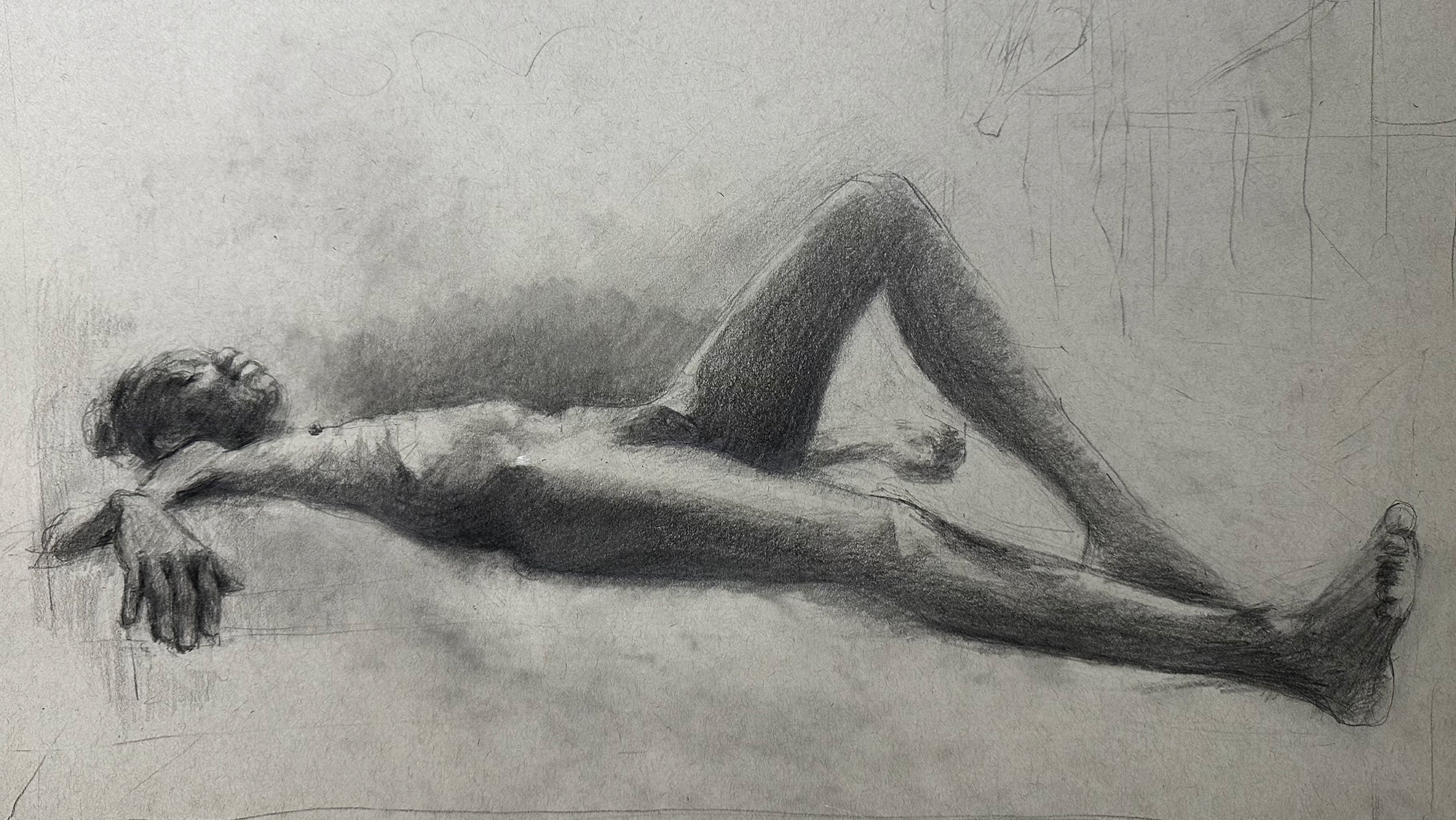

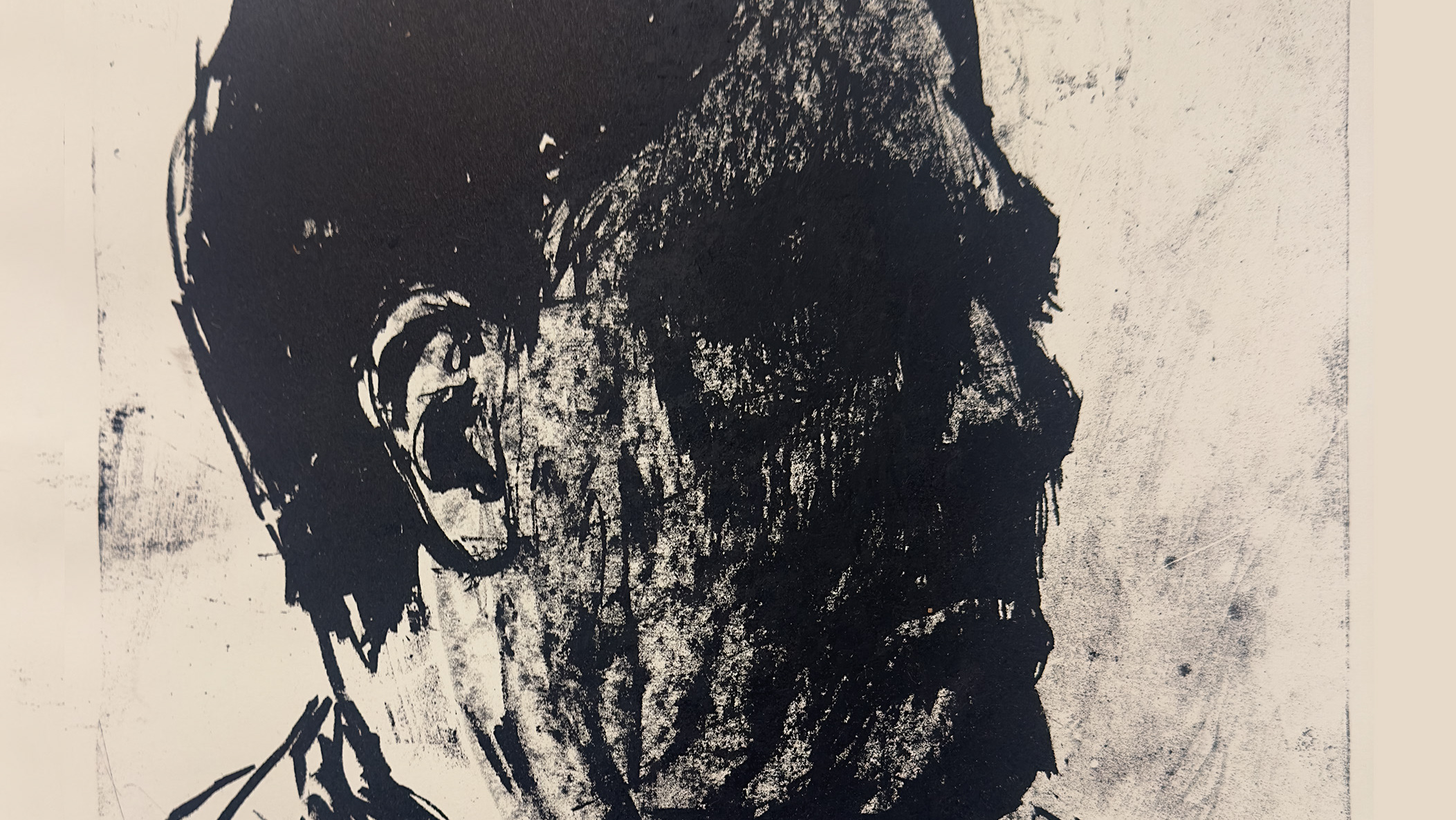

The specific drawing style I teach begins with teaching students to draw quickly and expressively from

sight (in the teaching style of my most influential professor, David Passalacqua), not only because

this style of teaching leads to expressiveness, mindfulness, and the flow state, but also because it

allows for the maximum amount of deliberate practice in any given time frame.

Once students know how to see like an artist and record what they see, I refine those abilities by

teaching anatomy, perspective, value structure, and design, using deliberate practice techniques.

Unfortunately, when students adopt a fixed mindset, the belief that intelligence or talent is innate,

they are unlikely to feel motivated enough to engage in deliberate practice or sustain focus long

enough to learn to enter the flow state. Students who have a fixed mindset, even if they believe that

they are innately “smart” or “talented,” quickly become risk-averse; they become afraid to make

mistakes, proving to themselves or others that they weren’t one of the chosen ones after all.

Individuals who have a growth mindset believe that effort leads to excellence, and they are right.

People with a growth mindset are likely to act on their belief system and put in the hours of hard work,

they are not afraid to fail and learn from failures, a key to deliberate practice and robust myelin

sheaths. Growth and fixed mindsets are both self-fulfilling prophecies.ix

My role as a teacher is to allow students to engage in rigorous, deliberate practice in the skills that

lead to expressive and accurate drawing, while teaching them to enter and sustain deep flow states so

they can access and express their creativity. An important aspect of this role is informing students

that they have endless, scientifically proven abilities to develop any skill, a mindset that provides

them with the motivation to work hard, take risks, and become exceptional draftspersons and

artists.

i iEricsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert

performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.3.363

ii Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi on flow [Dataset]. In PsycEXTRA Dataset.

https://doi.org/10.1037/e597022010-001

iii Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: the new psychology of success. Choice Reviews Online, 44(04), 44–2397.

https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.44-2397

iv ivEricsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of

expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.3.363

v vEricsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert

performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.3.363

vi Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi on flow [Dataset]. In PsycEXTRA Dataset.

https://doi.org/10.1037/e597022010-001

vii Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2013). Finding your element: how to discover your talents and passions and transform

your life. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB15674949

viii Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi on flow [Dataset]. In PsycEXTRA Dataset.

https://doi.org/10.1037/e597022010-001

ix Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: the new psychology of success. Choice Reviews Online, 44(04), 44–2397.

https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.44-2397